As I briefly mentioned in my last blog post, I’ve been on holiday! I went to Warsaw in Poland last week, just for a bit of a break, to see the Christmas market, go ice-skating, drink stupid amounts of mulled wine, eat my body weight in food everyday – just the usual things you tend to do at this time of year. Warsaw was lovely, especially the Old Town, however I couldn’t help but notice the amount of graffiti around the city. Everywhere. It was inescapable. And, of course, having recently studied the impact of graffiti in heritage issues and contemporary archaeology, it got me thinking about the relevance of graffiti in personal (and communal) expression and identity. (This inevitably made me feel guilty for not sharing what I’d been learning with you guys sooner but, you know, I had sights to see and waffles to eat so I soon got over that…)

I sadly (perhaps stupidly!) didn’t take any photo’s of the graffiti in Warsaw, but it was everywhere – even here in the Old Town!

Graffiti is often considered as anti-social vandalism, and largely remains studied by criminologists and sociologists. It is widely viewed as ugly, garish and damaging. Yet, if you get over the cultural stigma surrounding graffiti then it can tell you interesting things about the place you live – it can be used for political expression and social collaboration. Above all, it allows for artistic expression and gives often marginalised people a chance to engage in a kind of discursive practice which goes unnoticed by most people every day. In my opinion, if it is used for beneficial means then the power and expression elicited by graffiti should be respected and to an extent encouraged.

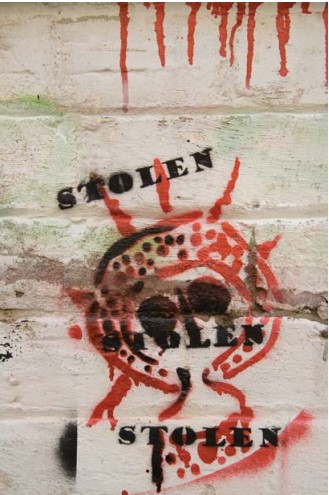

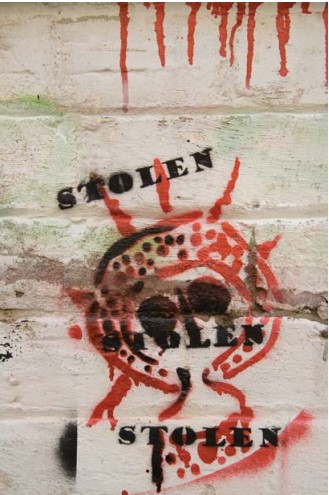

An example of graffiti in Warsaw. Photo by ROA ! on Flickr

A ‘Wandjina’ type stencil re inscribed with the word ‘stolen’. Photo by Ursula Frederick who studies the influence of looking at graffiti on understanding rock art and heritage issues in Australia.

So how does this help us in archaeology? Well if, as suggested by Ursula Frederick (2009, 212), you define graffiti as a “complex mark-making phenomenon” then studying graffiti has the potential to tell us about mark-making practices in the past. It may be possible shed light on the reasons behind mark-making, such as why prehistoric peoples made cup and ring marks? Was it part of a cultural tradition? Was it a way of saying ‘We were here!’? Or was it supernatural – linked to star constellations, or the movement of the moon? Questions like this bring me back to my ‘mini-project’ and Long Meg…

![IMG_2554[1]](https://theheritagesight.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/img_25541.jpg?w=750)

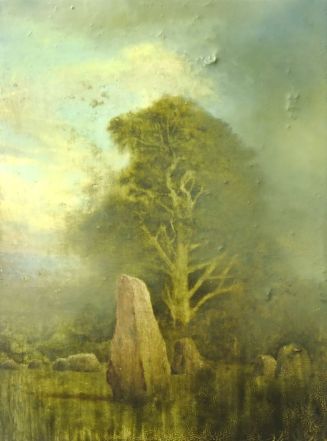

Long Meg features ‘cup and ring’ marks, frequently found across northern England.

Long Meg is special in that she features Neolithic rock art, something which is found widely across Britain, northern England in particular (read more about this

here). I’m going to be honest and tell you that I don’t actually know a lot about rock art, or ring and cup marks, or anything much about the theories on why prehistoric people chose to paint and carve things into cave walls and megaliths. I can still speculate though, and I hope you as readers don’t mind me doing so. Like modern graffiti, rock art across Britain has recurring motifs or styles. Whether there is a link between these styles, or what this might be if there is one, can be questioned. Like graffiti again they are often found on ‘public’, outfacing areas – on stone circles like at Long Meg, and cairns. They are public – but does this then mean that they aren’t secret? How do we know that the Neolithic people who made these marks weren’t also involved in a kind of secret discursive practice? How do we know that it wasn’t only a few members of Neolithic society which used these marks as a visual criticism on the politics of their contemporary society? What on earth could cup and rings be a criticism about I hear you ask… Well, I can’t answer that but I welcome any suggestions(!) Perhaps they were also viewed as destructive and ugly – damn those anti-social Neolithic people and their vandalistic ways!

Photo by DavidRBadger 2015 (Flickr)

Maybe, just maybe, they had no meaning at all, and it was just a way of passing time – a simple artistic practice passed on from one to another. Ursula Frederick (mentioned above) writes about the potential use of rock art research in looking at contemporary graffiti. She questions:

“How do we determine which marks made in the past were ‘legitimately’ produced and which ones effectively went ‘against the grain’ of accepted convention?” (2009, 229)

How indeed. The frequency of cup and ring marks across northern England would suggest that the ones on Long Meg didn’t go ‘against the grain’. So can we call them Neolithic graffiti? I say yes – it may have been an accepted practice, unlike graffiti today, but it has significant similarities with graffiti. It has a purpose, it has a visual presence which probably had a contemporary meaning, and it must have connected people together in a visual discourse which is, sadly, as inaccessible to us today as much of the discourse behind the graffiti in our towns and cities.

![IMG_2552[1]](https://theheritagesight.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/img_25521.jpg?w=750)

‘Cup and ring’ mark on the monolith ‘Long Meg’

Above all that, the rock art at Long Meg is simplistically beautiful, and like some graffiti, should be respected and not overlooked. I urge you to visit it if you get the chance. Let me know in the comments your thoughts on rock art/graffiti and also if I’ve made any sense with this post at all! It is a fascinating subject and one which I will endeavour to learn more about.

If you would like to read more, take a look at this lovely brochure by The Northumberland and Durham Rock Art Pilot Project on the ADS. There are more links to information on rock art in the brochure, as well as a link to The British Rock Art Blog. Check it out!

Frederick, U.K. (2009) “Revolution Is the New Black: Graffiti/Art and Mark-Making Practices.” Archaeologies 5 (2). Springer US: 210–37.

![IMG_2554[1]](https://theheritagesight.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/img_25541.jpg?w=750)

![IMG_2552[1]](https://theheritagesight.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/img_25521.jpg?w=750)

![IMG_2168[1]](https://theheritagesight.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/img_21681.jpg?w=578&h=578)