Many of you may know that six (!) weeks ago now I arrived back in the UK after spending my second field season at the Neolithic site of Ҫatalhöyük in southern central Turkey. I’ve been meaning to write a blog post about my experience on the site this year for a while now. Six weeks to be exact. But in the midst of graduating*, working full time, moving house (meaning a week and a half without internet *shudders*), and preparing to travel to Egypt at the end of September (more on that to come) I seem to have had very little time to actually sit down and write anything. Life, eh. Tonight however, after a much needed long soak in the bath (featuring candles and the Braveheart soundtrack. Of course.) I’m finding myself feeling relaxed and reflecting on how lucky I am to have been given the opportunity to work on such incredible site as Ҫatalhöyük not only once, but twice. And I feel like writing about it.

So where to begin? I would say that, first of all, Ҫatalhöyük is mind-blowing. If you ever get the chance to visit – go! From the wall paintings, burials and intriguing figurines, to the 20+ meters of excavated houses stacked on top of one another representing over 1000 years of human occupation – it will literally take your breath away. People come from all over the world to visit the site, which was designated in 2012 as a World Heritage Site, and speaking to visitors reminds you of how impactful archaeology, and the tangible remains of the past can be on people’s lives. It can bring people together in joint wonder and a desire to cooperate in understanding and interpreting our shared past. I believe that Ҫatalhöyük, more than many other sites, has the ability to do this – for both the visitors and the researchers who work there. And so I’m aware of how lucky I am to be a part of the Ҫatalhöyük Research Project’s Visualisation Team, to be a part of the bridge that connects the researchers and the visitors together in a shared understanding of the place, and to help bring new interpretations to a wider audience both on and off-site.

Looking towards the North Shelter at Catalhoyuk from the top of the mound with the Konya plain stretching out beyond.

The North Shelter from the Dig House. This view gives a good impression of the mound!

Inside the North Shelter – the archaeology here is incredible!

And so I find myself reflecting on what I’ve learned from working at such an internationally recognised site, which is hugely important to so many people, and how it has impacted me personally. The 2016 field season was, at times, a struggle for me, and I would say it was both completely different and exactly the same as my first field season. I experienced the same apprehensive feeling before travelling there, the same sense of awe at the scale and richness of the site once there, and the same feeling of pride at what we’d achieved on leaving. Yet, inevitably, many things were different. I was working with a completely different team, being the only returner bar our fabulous director Sara Perry and our incredibly talented graphic designer, Ian Kirkpatrick (you guys are awesome!). And with this came new highs and lows; the joys of getting to know three new colleagues, seeing their passions, working with and alongside them, and watching their love, enthusiasm and awe for the site grow to match my own. This was probably one of the things I enjoyed the most about being at Ҫatal this year. Between us we achieved a HUGE amount, collaborating with many others from the wider international Ҫatalhöyük Research Project to write blog posts, social media post for Twitter and Facebook, produce a new family trail, design and print new signage in the Visitors Centre, create videos, host a game jam, and develop ideas for the interpretation of four new Replica Houses which are in the process of being built on the site. (Look out for the 2016 Archive Report in the new year for full details on what we did). And as well as this many of us, including myself, worked on our own projects and dissertations. During the 2015 season I took over the task of collating and analysing the visitor data, the results of which you can read in the 2015 Archive Report, and I carried this on this year with the hope that I can use it for the publication of my dissertation (I’m getting round to telling you all about this, I promise). And so we were a busy team – a whirlwind of fun, laughter and hard work for two weeks!

Heritage Superheroes! The Visualisation Team 2016 + friends: from left to right Tara, Izzy, Joka, Burcu, Levent, Ian, Dena, Ali, me and Sara. There was never a dull moment with this lot!

We were a fun-loving international team from Ege University (Turkey) and the University of York (UK). And between us we struggled to take a serious photo! From left to right: Burcu, Dena, Izzy, Sara, me and Tara. (Photo by Ali)

Yet amongst all the happiness and laughter I experienced some emotions which were not so welcome, and which I hadn’t felt as intensely last year. Mostly doubt in my skills as a heritage professional, and my contribution to the project. I realised I’ve written about this feeling before, when talking about completing my dissertation, and I have a suspicion that I’m not the only recent graduate who has felt this way working in the field. And it’s probably not the last time I’ll feel it. But reflecting on this has made me realise it was probably a natural reaction to working with such talented, incredible colleagues and one which I perhaps shouldn’t have allowed myself to fall victim to. Competition is a funny thing, something I will no doubt have to deal with at varying points in my career (we’re all human, right?!) – and so I shouldn’t have let it detract from recognising the things I did achieve and the skills I do have.

Ҫatalhöyük can sometimes seem an intimidating place for someone just starting out in heritage and archaeology – not only because of the world-class archaeology, it’s reverence in the archaeological world and its lasting legacy on this, but also because of the standard of intellectual and academic practice which goes on there. It is filled with incredible people, both national and international, and the opportunity I’ve had to be around these people will no doubt have a lasting impact on my career trajectory in the heritage sector. I can already tell that Ҫatalhöyük has pushed me to overcome personal trepidations and given me a desire to learn new skills and try out aspects of heritage interpretation that I never thought I would. But mostly it has taught me to have confidence in my abilities, and not to let that confidence get knocked in an environment and sector where it could so easily get lost. And finally, it has taught me to value the support and friendship of my colleagues and peers who probably, more often than not, are feeling exactly the same way.

I feel like there’s a lot more I could say about my experience of working at Ҫatalhöyük, and I’m aware that it is my only real experience in the field to date (minus two weeks in deepest Wiltshire excavating a Roman villa which I’ve forgotten most of and feels like years ago). But even though I’m aware that the impact that it has had on me so far has been huge, I’m also aware that it is one site of many, and one project of many, that I will hopefully work on – and I have a lot more to learn. And so it will be interesting to see whether my next fieldwork – at the site of Memphis in Egypt for a whole three months (!) – will equate to my experience at Ҫatal. Something tells me it will and it won’t, but whatever my experience will be in Egypt Ҫatalhöyük has set me in good stead to deal with whatever comes my way, both in terms of working as a team and dealing with my own apprehensions. And for that, along with many other reasons, Ҫatalhöyük will always be a special place for me!

Below are a few of the many photo’s we took this year (there were so many to choose from!) – of the Visualisation Team in action and having fun… Hopefully it will give you an idea of the kind of work we do and just how incredible the site is! (Warning: there will be selfies)

More team photos posing in front of the mound. Left to right: Tara, Dena, Izzy, me, Sara and Ian. (Photo by Ali.)

In our spare time after dinner we went for many walks off-site… (Photo by Sara)

…And saw many beautiful Turkish sunsets.

The were also a great chance to take many team selfies! (Although we never needed an excuse!)

We spent a lot of our time looking over existing signage and discussing where we could improve it. (Photo by Ali)

Me attempting to install signage in the on-site Experimental House. (Photo by Ali)

We hosted the Great Catalhoyuk Game Jam, hosted by Tara! Some great game ideas were developed, including a Neolithic Tinder game and a Catalhoyuk adventure game with some questionable conclusions… (Photo by Sara)

This year we had some little additions to the Catalhoyuk Team, Clay Balls (above) and Mr Pickles. They provided much needed stress relief when we needed it!

The team installing our new signage on our last evening on site. Down to the wire as always! (Photo by Dena)

Our wonderful Turkish team member Burcu and I removing an existing interpretation panel in the Visitor Centre. (Photo by Dena)

Installing the new signage! (Photo by Dena)

Following a crazy, wonderful, often stressful and always enjoyable two weeks on site we flew back to the UK satisfied that we’d achieved way more than we ever expected to!

*blog post about this to follow soon.

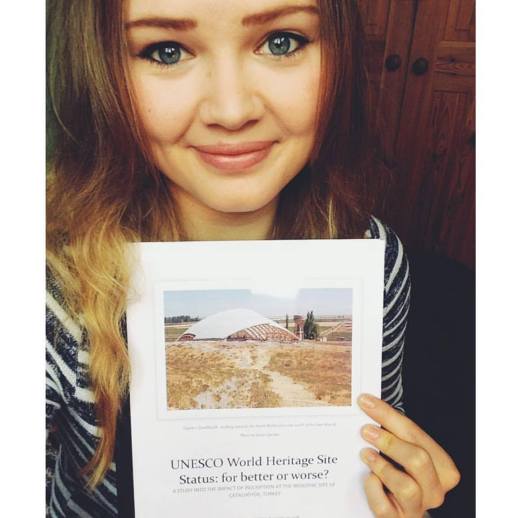

![IMG_2554[1]](https://theheritagesight.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/img_25541.jpg?w=750)

![IMG_2552[1]](https://theheritagesight.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/img_25521.jpg?w=750)

![IMG_2168[1]](https://theheritagesight.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/img_21681.jpg?w=578&h=578)

![IMG_2168[1]](https://theheritagesight.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/img_21681.jpg?w=750)

![IMG_2169[1]](https://theheritagesight.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/img_21691.jpg?w=750)

![IMG_2170[1]](https://theheritagesight.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/img_21701.jpg?w=750)

![IMG_2167[1]](https://theheritagesight.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/img_21671.jpg?w=750)